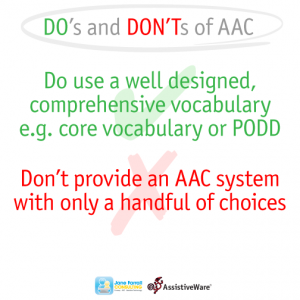

In May this year David Niemeijer from AssistiveWare and I did a presentation at the AGOSCI Conference on the Do’s and Don’ts of Implementing Real Communication Through AAC. We created a poster to accompany that blog post – and this is one of the follow ups to the poster.

One of the things I do every 6 months (or so), is I download all the AAC apps I can find from the App store, evaluate them and then add them to my list of AAC apps (Updated to add: the AAC apps list has been discontinued).

Every time I do this update, one or more of the new apps describes itself as a “beginning AAC app” or an app for “beginning communicators”. I frequently give these apps, along with the apps that describe themselves as “for the lowest functioning” one star – the lowest rating I give. This sometimes results in an email from the app developer, questioning my rating of their app. I’d like to explain why I rate them like this.

The phrase “Beginning AAC” in this context, often seems to me a euphemism for poor practice in AAC. These apps often only have a small number of words; the vocabulary has a heavy emphasis on nouns; there is no symbol system included and the user has to import all their own images; the vocabulary is arranged in categories; and sometimes there are also limited options for expansion or customisation. The app is often accompanied by phrases like “small number of symbols, as needed by beginning communicators” or “photograph based to simplify for early AAC users”.

So much of what is contained in these apps is NOT beginning AAC – but AAC that doesn’t promote language and communication development. The statements in the app descriptions feed into this poor practice – and live in a world where the phrase “presume competence” has never been heard.

Having said all of that, what DO we know about beginning AAC?

Symbols

There is no evidence that the often referred to “symbol hierarchy” has any relevance in AAC implementation – or even that it operates as some people think it do (and as I was introduced to it in my speech pathology degree nearly 30 years ago).

Romski and Sevcik (2005) refer to this as one of the myths of “Augmentative Communication and Early Intervention”. They summarise this myth with the statement “during early phases of development, it may not matter if the child uses abstract or iconic symbols because to the child they all function the same.” Porter and Burkhart (2010) greatly expand on this, putting the case very strongly in terms of us needing to do aided language stimulation to help an individual learn what a symbol means. DaFonte et al (2008) agree that “there does not seem to be a hierarchy of aided-visual symbols” and add that “experience plays a significant role in learning aided-visual symbols and generalizing their usage”.

So – to go back the topic of beginning AAC there is absolutely no need to limit ourselves to an AAC system that can manage objects or photographs when making AAC decisions – and those AAC apps that state that there is are subscribing to a myth.

Amount of Vocabulary

At the ISAAC Conference last year in Lisbon, Professor Pat Mirenda gave a pre-conference workshop on “Autism Spectrum Disorder and AAC”. During this workshop she reviewed the current state of what we know about AAC as it related to individuals with ASD. One of her lines from her handout really rang true for me – and not just for individuals with ASD:

“WE USED TO THINK: Start with just a few (4-6) picture symbols and add a few more at a time, as the student with ASD shows that he or she can communicate appropriately with them usually by requesting

Now we think: Really? Where is the research that defends this practice?

This is certainly not how other kids learn new words and acquire language.”

Mirenda, 2014

For individuals to learn language, we need to provide not just a few picture symbols – but a wide range of symbols that represent a robust vocabulary that supports them to learn how to put words together, supports them to contribute in every situation and supports them to develop into an autonomous communicator. This vocabulary needs to consist of a range of parts of speech – they need adjectives, verbs, adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections, determiners and even some nouns (but go easy on the nouns). Try using a well designed core vocabulary system or Pragmatically Organised Dynamic Display (PODD)

To once more return to the topic of beginning AAC, there is no evidence to support starting with only a few symbols and those AAC apps that say there is are adding to yet another myth.

So how does this turn into autonomous communication?

For any individual to learn how to use their well designed AAC system with robust vocabulary represented by picture symbols we need to make sure that we introduce AAC in a way that helps them to become an autonomous communicator. This can happen with a range of strategies – but it has to include aided language stimulation (Goossens’, Crain & Elder, 1992). By using the individual’s AAC system to initiate, respond, negate, continue, greet, wrap-up and all the other conversational turns we take, we show them how they can do it. By using their AAC system for real reasons, we show them what the symbols mean. We might need to do this for some time before the individual starts doing it (remember – we talk to infants for around 18 months before they start speaking) – but aided language stimulation is absolutely part of the road to good communication. It has been shown to increase receptive vocabulary – which totally makes sense (Dada & Alant, 2009) as well turn taking (Beck et al, 2009) and other communication skills. And in a cyclical pattern that validates this – unless you have a good robust vocabulary you can’t do aided language stimulation.

So – for any of those AAC apps that claim they are for a beginning AAC user we need to try having a conversation with them. Can you have a chat with a partner or friend? Can you ask a question at school? Can you change topic? Can you keep this going through multiple communication turns? If you can’t use it yourself to talk with, how can you do aided language stimulation? And how do we expect a beginning communicator to communicate with something a competent communicator can’t use?

So what is beginning AAC?

Interestingly, good beginning AAC looks an awful lot like later AAC. Every individual with complex communication needs requires a comprehensive vocabulary that lets them say what they want to say, wherever they want to say it, to whoever they want to say it. The difference is that in beginning AAC, everyone around the individual with complex communication needs to use the system, as much as possible, to demonstrate how the system can be used and to teach them the meaning of the symbols. As times goes on the individual with complex communication needs begins using the system themselves – and this use increases. Without these components of: 1. a robust vocabulary; 2. represented by symbols; and, 3. lots of aided language input we are not doing the best we currently know how by each and every beginning communicator. This may be different from what you believe – but if you think that beginning AAC involves only a few photographs or objects of reference ask yourself the same question Professor Mirenda asked at ISAAC – “Really? Where is the research that defends this practice?”

PS If you’re really interested in how I rate AAC apps – it’s at the bottom of every page of my AAC apps lists (Updated to add – the AAC apps list has been discontinued).

References

- Beck, A. R., Stoner, J. B., & Dennis, M. L. (2009). An investigation of Aided Language Stimulation: Does it increase AAC use with adults with developmental disabilities and complex communication needs? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25 (1), pp. 42–54.

- Dada, S. & Alant, E. (2009). The impact of an aided language stimulation program on the receptive language abilities of children with little or no functional speech. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 18(1), 50-64.Da Fonte, M. A., Thurber, M., Chae, S., & Lloyd, L. L. (2008, November). Is there a hierarchy of aided visual symbols? A review of the literature. American Speech Language Hearing Association (ASHA) Convention: Celebrating the Winds of Change. Chicago, IL.

- Goossens’, C., Crain, S., & Elder, P. (1992). Engineering the preschool environment for interactive, symbolic communication. Birmingham, AL: Southeast Augmentative Communication Conference Publications.

- Mirenda, P. (2014, ). Autism Spectrum Disorder and AAC. Session presented at the 2014 International Society on Augmentative and Alternative Communication Conference, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Porter, G & Burkhart, L. (2010). Limitations with Using a Representational Hierarchy Approach for Language Learning. Retrieved from http://www.lburkhart.com/handouts/representational_hierarchy_draft.pdf

- Romski, M.A. & Sevcik, R.A. (2005) Augmentative communication and early intervention: myths and realities. Infants and Young Children 18 (3), 174

Alicia Garcia

jane

khowery

jane

Alicia

jane

Carole

jane

Jodi Altringer

jane

Vanessa Southard

jane

Jodi Altringer

jane

Pingback: Comprehensive Literacy Instruction: Meeting the Instructional Needs of ALL Students in our Classrooms | Jane Farrall Consulting

Micaiah

jane

Nikolaus F Englen

jane