30 years ago, in 1991, I became a speech pathologist. Very quickly, I became heavily interested in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) and started to work more and more with individuals with complex communication needs.

In the beginning, I wasn’t very good at implementing AAC – partly because I was such a new graduate and partly because the field was still learning an enormous amount about what we should do!!

The first big change that happened in my AAC world, changed me forever as a clinician. Carol Goossens’ visited Australia and talked about aided language displays and that we needed to “speak AAC for individuals to learn AAC.” This was a completely new concept for me – and for those I worked with. We started making aided language displays, using them in multiple situations – and we saw many individuals with complex communication needs really blossom as communicators. Carol taught us so much – from how to engineer the environment for communication success, to thinking about the range of vocabulary needed in a situation for an individual to participate and to have multiple communication turns. (See Goossens’, C., Crain, S., & Elder, P. (1992) for more information)

The next big change that came along, was PECS. It started being used in Australia in the mid to late 90s and quickly gained a lot of popularity in use with autistic students. PECS came at communication from a completely different perspective to the approach introduced by Goossens’. Where aided language displays were based in natural communication interactions, “PECS relies on the principles of applied behavior analysis (ABA) so that distinct prompting, reinforcement, and error correction strategies are specifed at each training phase in order to teach spontaneous, functional communication.” (Bondy & Frost, 2001, p.728).

And so, in the late 90s I attended PECS training, listened to their rationale and started implementing it with some students. Compared to aided language displays, I saw a smaller number of individuals where PECS made an impact on their communication – and for many of them the initial positive changes were often negated over time by other changes. For example, the structure of PECS teaches an individual to request – and sometimes the ability to request and receive their favourite items reduces challenging behaviour. Over time, you fade the requests so that students “don’t always get what they want”. At that point, we often saw a big increase in challenging behaviour again – and the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. At no stage in PECS do we teach an individual how to protest or reject in a socially appropriate way.* So – once we got to the stage where we were having to tell an individual that they couldn’t get items every time they requested them, they had to revert to body language, facial expression and behaviour to express their dissatisfaction with this change! This was not ideal. And so, due to the limited positive outcomes and the unfortunate negative outcomes, I started to use PECS less.(*Edited to add that I have now had a number of people tell me that PECS does, in fact, include a way of teaching saying “no” at Stage 3 so my apologies for being so definite that that was not in the program.)

Meanwhile, the rest of the AAC world was developing. More varied and well designed AAC systems were being developed. We were getting more and more information about how to introduce and implement them in ways that help each individual move towards becoming an autonomous communicator. Today we have a number of well designed systems and options and a constantly growing evidence base around using AAC.

A few years ago, when asked my opinion of PECS I would say “I only use it with a very small number of students with autism. There’s no evidence base for using it with other groups. The meta-analyses which review PECS are very mixed and not overwhelmingly positive. I also believe that for any individual PECS would only ever be an introductory system because it doesn’t have a range of language available, so it doesn’t support individuals to be independent, autonomous communicators.” And then, because people would often tell me that PECS teaches more than requesting – I would usually specifically mention that it never teaches protesting or rejecting and that that is a skill we all need to learn to do in a socially acceptable way.

(And, if you are unsure what a meta-analysis is, please read the information at this link.)

Recently, I have been thinking more about PECS again. It’s been several years since I’ve used it. I find good comprehensive AAC systems give individuals with complex communication needs better outcomes. They provide language for them to communicate with all the different communication functions that we need across the day, and because we can implement them in a naturalistic way through aided language stimulation, individuals learn how to use that language in a range of contexts and settings – in the same way everyone else learns to communicate.

And before I go any further I want to explain that when considering any clinical intervention as a speech pathologist, we use three elements together to make a decision based on evidence based practice. These are shown below.

One of these circles is the reason that I have returned to thinking about PECS. This is the circle called “client perspectives” – and there is currently a steady dialogue coming from autistic people about ABA and programs like PECS which are based on the principles of ABA. If you haven’t caught up with this you can read about it online – and this is one article which gives a balanced summary.

So, if autistic people are telling us that ABA and programs based on ABA principles, like PECS, are restrictive practice, should we still be doing PECS? One therapist asked this recently in a Facebook group I am in – and was deluged with a mix of positive and negative feedback. I noticed that a lot of people had opinions – but very few people’s opinions were based on anything other than their personal experiences in which they stated that PECS did or didn’t work or how much they did or didn’t like it. And while clinical expertise is one of the three components of evidence based practice, we are also supposed to use best external evidence as well.

So, as part of my inner musings about PECS, I decided it was time to look at the evidence base again. A few years ago, when I looked at the meta-analyses which focused on PECS, I found very mixed results and opinions about outcomes and efficacy. However, recently the National Disability Insurance Agency (here in Australia) has commissioned a report into the best available high-quality evidence about interventions for children with autism aged up to 12 years. The report is published by the AutismCRC, and you can access the report via https://www.autismcrc.com.au/interventions-evidence.

The team of researchers involved in writing and compiling the report have thoroughly reviewed the evidence in Interventions for Children on the Autism Spectrum. As part of this, they have even done an Umbrella Review – which is basically a meta-analysis of a group of meta-analyses. Their stated aim is “to support consumers to make informed choices about which intervention may best suit the needs of their family”.

If you download the full report, you will find pages and page of information. But the parts that interest us for this blog post, are the summary tables.

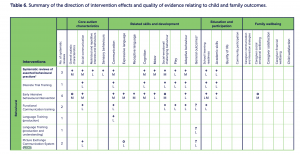

The table above includes the information about PECS. Since PECS is based on ABA it is included with behaviour interventions. You can see that PECS has:

- a positive therapeutic effect on social-communication, low quality evidence

- a null therapeutic effect on expressive language, low quality evidence; and

- inconsistent therapeutic effect on general outcomes, low quality evidence.

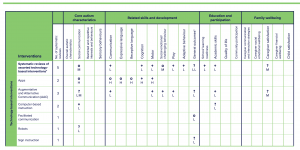

And the table above includes the information on all other forms of AAC except PECS.

You can see that AAC (except PECS) has:

- inconsistent therapeutic effect on social communication, low to moderate quality evidence

- positive therapeutic effect on communication, low quality evidence

- positive therapeutic effect on motor skills, low quality evidence

- positive therapeutic effect on social-emotional/challenging behaviour, low quality evidence

- positive therapeutic effect on play, low quality evidence

- inconsistent therapeutic effect on general outcomes, low quality evidence

- positive therapeutic effect on academic skills, low quality evidence

- inconsistent therapeutic effect on caregiver satisfaction, medium quality evidence

This list and the table clearly show that the evidence is much stronger for using all other forms of AAC – other than PECS. (Although it also shows we still have a long way to go.)

So, from today if anyone asks me about using PECS I will now reply: “I don’t use it anymore. The evidence base for autistic children is much stronger for all other forms of AAC – and that’s what I use.” It’s a much more definite statement than I’ve made before – but I feel very supported to say this with the weight of the evidence base – client perspectives plus clinical expertise backed up by external scientific evidence – behind me.

And to finish this blog post, I’d like to come back to my original question.

Why are you using PECS?

References

Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (2001). The Picture Exchange Communication System. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 725-744. doi:10.1177/0145445501255004

Goossens’, C., Crain, S., & Elder, P. (1992) Engineering the Preschool Environment for Interactive, Synbolic Communication. Birmingham, AL: Southeast Augmentative Communication Conference Publications

Whitehouse, A., Varcin, K., Waddington, H., Sulek, R., Bent, C., Ashburner, J., Eapen, V., Goodall, E., Hudry, K., Roberts, J., Silove, N., Trembath, D. (2020). Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence. Brisbane, AutismCRC

Susan Berkowitz

jane

Laura Taylor

jane

Barbara Coven-Ellis

jane

Mary

jane

Erin Troost

jane

Lilo Seelos

Jill Stein-Wirth

jane

Laura Coakes

jane

Emma

jane

Amanda

jane

Collette

jane

Harriet Korner

jane

Harriet Korner

Connie

jane

Claudia Marimón

Julie

jane

Julie

jane

Andy Bondy

jane

Andy Bondy

jane

Andy Bondy

Catharine

Laura Hayes

Jane M

jane

Michelle Britt-Thompson

jane

jasamp

Andrew Stokes

jane

chrissiecan

jane

Brenda

jane